Before you begin to support someone with ambiguous loss, make sure you understand both “loss (definite loss)” and “ambiguous loss”.

The JDGS website “Supporting those who have lost a loved one by death”, as well as sections of this website, can help you understand this better.

“Ambiguous loss” can also be a “complicated loss” because of a complicated situation. Complicated situations create complicated grief. Some people may not be able to move forward at all, and others may become depressed.

However, that does not mean that the person is abnormal. It is the complicated situation which is abnormal. First, understand the person’s situation without assuming that their thinking is wrong or that they have a problematic symptom.

Living with “ambiguous loss” can be very difficult for any person.

Support from relatives and friends

Support from family, relatives and friends is one of the most important forms of support. That is because they are the people who know the suffering of the family and how much they care about their loved ones who are not here right now.

You may not know what to say to that family. You may also feel sad when you see a sad face or a suffering figure, so you may want to avoid them as much as possible. But in many cases, it is better to tell the person that “I am sad and very sorry” rather than to say nothing or avoid the topic at all.

You can’t take away their grief, but you can support them by listening to them when they want to talk and helping them with their real needs.

Learn about “ambiguous loss” before you go into support. Then you may be more prepared to support those who are in pain.

Please take a look at the “What is ambiguous loss?” section.

A few ways to help

1.Just be there

It takes time for any person with an “ambiguous loss” to manage themselves. That period can be very painful. If you ask the person and they allow you to be with them, it is often helpful to just be there without saying anything.

2.Listening

For those who are in pain with ambiguous loss, talking to someone who listens to them is a big help. A free expression of emotions, such as sadness, anger, or bitterness, can help them relieve anguish.

Each person’s way of dealing with loss is different. They have the answer to how to come to terms with his or her grief. Especially in the case of “ambiguous loss,” it’s perfectly fine that the person deals with it in their own way. Respect the person’s thoughts and answers as they come up in the conversation, even if they are different from yours.

3.Respect those who are not now with family

The missing person is still an important member of the family. Celebrating their birthday or having the opportunity to get together for them could provide great support for the family. Through such support from those around them, the family can feel that “the person” and “they” themselves are being respected.

4.Other helpful support

The family may be mulling over and over again about what has happened. That’s normal in the process of coming to terms with such a situation.

Tell the family to take care of their own bodies. Tell them to eat well, get the rest they need, and see a doctor if they have any health concerns. If possible, take the time and discuss what you can do to help.

People experiencing “ambiguous loss” are concerned that there is something wrong with their inability to cope with the loss. At the same time, they are either consciously or unconsciously afraid of the comments made by those around them. For example, if a family member is missing, “It’s about time you move on…” and so on. It is said that due to this fear, people who have had such a loss often alienate the people around them.

In an “ambiguous loss,” no one can fully determine that loss. That is a fact. Those who support them should provide support on that basis. It is not helpful to try to reduce their anxiety by encouraging them to think in “black and white”, or trying to “leave them alone” by acting like the loss never happened.

Information and psycho-education are important ways to support “ambiguous loss.” One needs an understanding of the hardships of the situation in which the family is placed. Examples include “It’s quite normal to feel that you can’t accept your loss, that it’s hard to move forward. It’s not like there’s anything wrong with you,” and, “It doesn’t matter if each person has a different view from the people around them, even within your family.” It is said to be important to remind them of these things over and over again.

You should also help them gradually reconnect with people they feel safe with. Connecting with such people can be very helpful when someone is coping with ambiguous loss on their own.

Whether it’s “leaving without goodbye” or “goodbye without leaving”, the family suffers greatly from the ambiguity of the circumstances of loss. Because each family member perceives loss differently, the topic of loss may be avoided within the family, making it difficult for them to support each other.

Although everyone in the family is grieving deeply, one is crying in the bath and the other in their bedrooms, each alone. It is a condition that can cause the family to fall apart. As a result, this decline in family functioning can stall the grieving of each family member. Dr. Boss notes that loneliness and isolation, even within the family, makes recovery from ambiguous loss more difficult.

Dr. Boss provides support of ambiguous loss from a “family therapy” standpoint. For example, how has the family changed as a result of the ambiguous loss, how the family functions today, how has the role of each family member changed as a result of the loss, and how has the family’s daily life and mourning rituals changed? Facilitating the family to talk about these things together helps them live better as a family.

The“family therapy” approach, focusing on the family as a whole rather than on individuals, can be extremely effective when we support those suffering from“ambiguous loss.”

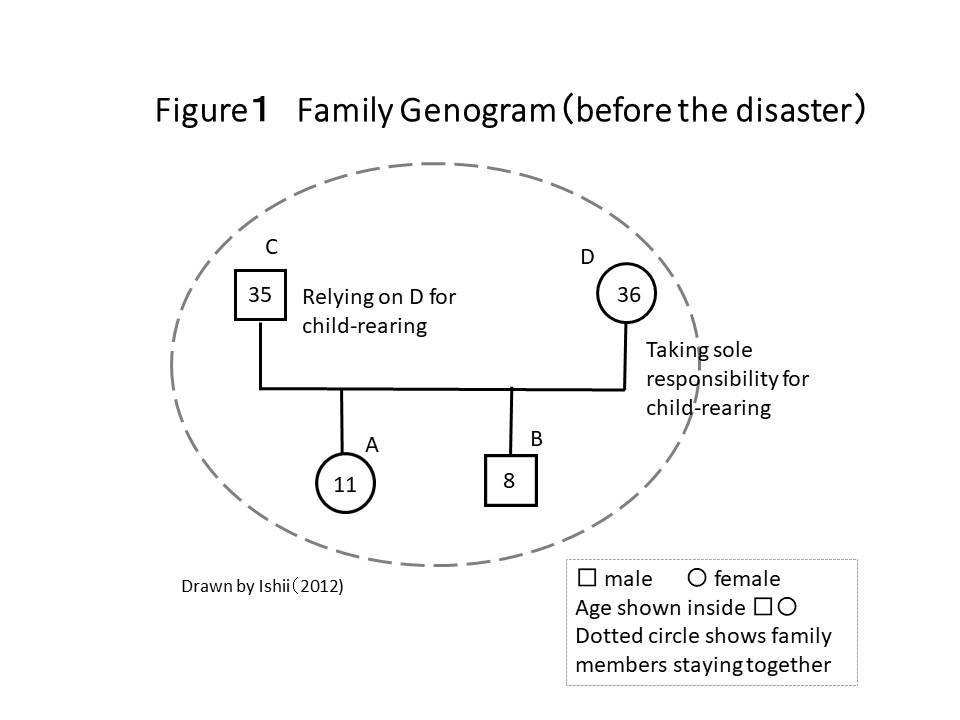

Dr. Boss recommends using a genogram, also known as a multigenerational family map, to understand and assess a family who is experiencing ambiguous loss.

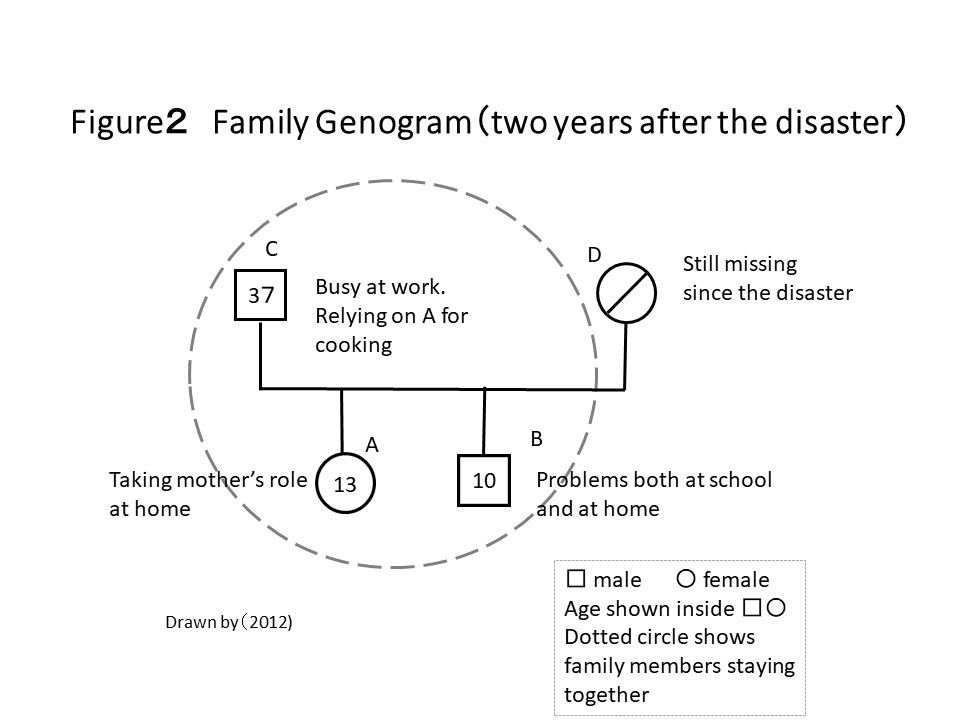

Comparing the two genograms before and after the disaster (or before and after the serious event) , we can see the changes that took place in the family. It highlights, for example, how families living together changed after the disaster and how their roles were altered.

For example, Figure 1 shows the genogram of a family of four (father, mother, daughter, and son) before a disaster. (This is not a real case.)

When the mother goes missing due to a disaster, as shown in Figure 2, the daughter (oldest child) may assume the role of the mother to help the family’s plight. On the other hand, if the condition continues for a long time, it is necessary to consider the impact on the entire family, including the sibling relationship and the parent-child relationships.

If you draw a genogram and look at the whole family as a unit, you may see problematic behavior in other family members (e.g., the son, the younger child) in the shadow of his sister’s hard work. When the son is viewed from an individual’s perspective, he is often seen as a “troubled child,” but when the genograms are compared, it becomes apparent that the relationship is deeply related to the family/sibling relationship and mutual roles that have changed significantly since the disaster.

For example, the boy may be repulsed by the fact that his sister, whom he had been close to, suddenly treats him with a parental commanding tone after the disaster. The boy who was confused by his mother’s being missing and lost his sibling relationship with his sister, with whom he was supposed to be able to talk about his feelings, may be expressing grief in the form of “problematic behavior”. After a few more months, the father may become more directly involved in dealing with his son’s problematic behavior and this may lead to another change in the role of the older sister. The gradual change in family relationships, starting with the boy’s problematic behavior, can be expressed as family resilience, even though it may seem like a problem.

By looking at the genogram of a family experiencing ambiguous loss, we can think about support from the perspective of the family’s developmental stage, focusing on the resilience of the family.

When supporting those who have been experiencing ambiguous loss, it may be important to sort out just “what the person has lost”.

For example, let’s say one is forced to evacuate from their hometown due to a nuclear accident. What has that person lost?

You might consider the following.

There may be much more.

Dr. Boss says, “People can’t grieve until they are clear about what they have lost. Working with them to identify the numerous losses they have experienced may cause them stress, but it can conversely lighten their burden and reduce that stress. Through such work, professionals and supporters are able to work through their grief.

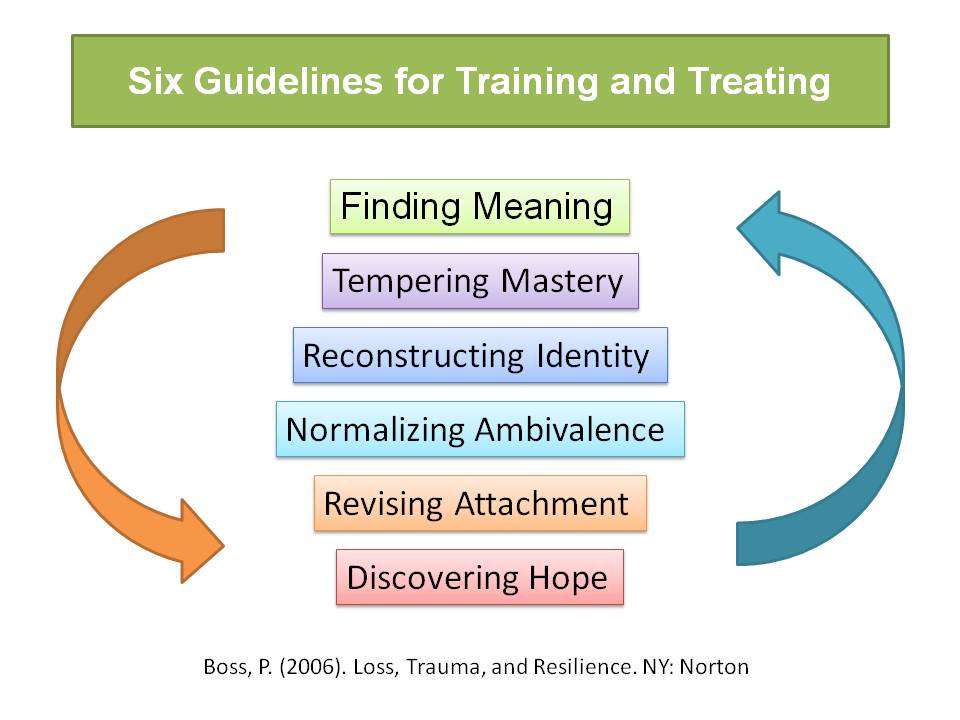

Dr. Boss has made a list of the following six guidelines for interventions to be undertaken by supporters.

These six guidelines are not linear, but move in a circular fashion, going back and forth. These six guidelines are explained in detail in the book, “Loss, Trauma and Resilience” (published in 2006/ Japanese translation in 2015).

1.Finding Meaning

<Helpful points>

2.Tempering Mastery

<Helpful points>

3.Reconstructing Identity

<Helpful points>

4.Normalizing Ambivalence

<Helpful points>

5.Revising Attachment

<Helpful points>

6.Discovering Hope

<Helpful points>

Everyone has the power to heal themselves from difficult situations. Its power has been termed as “resilience” in recent years. How to support this resilience is also key in ambiguous loss.

Most people in any state of “ambiguous loss” are able to cope with it with through the support of their families and communities. In order to do this, it is important to work from a “family therapy” perspective, to reestablish their family ties, as mentioned earlier.

It is also extremely important to create a “peer support” group in the community, whose members have gone through a similar experience in order to create a place offering trustworthy information and emotional security.

Dr. Boss also held group meetings for families of missing persons in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States, bringing them together and helping many people recover. For a summary, please refer to the page “Support after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York” in this corner.

After the terrorist attacks in New York City on September 11, 2001, Dr. Boss was asked by a building services company at the World Trade Center to care for the families of those who had gone missing there.

Thirty-two days after the attack, the first meeting for the families of the missing was to be held by a team of therapists from Minnesota and New York who had been convened.

Training was provided to the therapists prior to the family meeting. The training began with a theoretical perspective on ambiguous loss and the different reactions and challenges it can cause, and was incorporated into the therapists’ own work on ambiguous loss reflection before the sessions, as well as a deeper understanding of their cultural background.

At the family meetings held after that training, the following guidelines were adapted.

etc.

The family members who attended the meeting said:

“This has been a great help.”

“I feel that today people listened to my pain and understood my situation.”

“This was the first time I’d ever spoken about this in front of my children. It was very important to me.”

Dr. Boss notes that PTSD treatment alone is not enough when it comes to helping families of missing persons. While it is important to refer people with serious psychological problems to the appropriate professionals, many other people can recover on their own if they have an environment in which they can feel understood and accepted.

After the 9.11 terrorist attack, many families of the missing took the next step after attending family meetings coordinated by Dr. Boss.

<Reference>

Pauline Boss, et.al.: Healing loss, ambiguity, and trauma: A community-based intervention with families of union workers missing after the 9.11 attack in New York City. J Marital and Family Therapy. 29(4). 455-467. 2003.

The situation and the psychological processes of recovery are different between a state of “definite and authentic loss”, such as that of a bereaved family, and a state of “ambiguous loss”, such as that of the family of a missing person.

JDGS members were in contact with Dr. Pauline Boss soon after the disaster, and in March 2012, they had the opportunity to attend a training in person in the United States. At that time, Dr. Boss specifically emphasized that “ambiguous loss” needs to be framed very differently than “bereavement loss”, where death has been identified.

It is difficult for a family with “ambiguous loss” to come to terms with the loss as long as the situation continues, and the family must live with the ambiguity of the loss for the rest of their lives. It’s important that the supporters first understand their situation.

Another major problem that people in the midst of ambiguous loss often experience is isolation. Typically, many people in society, as well as supporters and so-called professionals, do not know what to say or how to support those who suffer from ambiguous loss. As a result, it is inevitable that some will keep their distance or use inappropriate language.

It is very important for professionals to know what these families with ambiguous loss are experiencing and how to support them.